Xi Wang Mu’s Curriculum Vitae

Date of Birth: All time, no one knows her beginning and no one knows her end

Place of Birth: Cauldron of Creation

Age: Timeless, Nameless

Place of Residence: Kunlun Mountain, energy behind all masks, yin essence

Occupation: Alchemist, controller of cosmic forces, time and space, the grindstone and five shards or bushels, especially the great dipper constellation. Keeper of the cosmic ladder, guardian of yin essence, savior, protector, healer in times of drought and political disarray, psychic healer, weaver of destiny of the universe, ultimate source of teachings transmitted by female sages, keeper of the Garden of Western Paradise, guardian of the immortal peaches, the peach tree, the world tree.

Aliases: Queen Mother of the West, Metal Mother, Metal Maiden, Jade Maiden, Spirit Mother, Rainbow Bridge, Golden Mother of the Shining Lake, Primordial Ruler, Mother of Tortoise Mountain, She of the Nine Numina and the Great Marvel, Perfected Marvel of the Western Florescence, the Ultimate Worthy of the Grotto Yin. Spheres of Influence: Multiuniverses, life, death, the afterlife, immortality, disease and healing, divine realization, interspecies communication, initiation of spiritual seekers, soul retrieval, throat singing, ecstatic dancers and singers connected to the great wellspring of Taoist mystics, hidden time and vast cosmic cycles, magic squares and compass rings, equalization, self-realization.

Spheres of Influence: Multiuniverses, life, death, the afterlife, immortality, disease and healing, divine realization, interspecies communication, initiation of spiritual seekers, soul retrieval, throat singing, ecstatic dancers and singers connected to the great wellspring of Taoist mystics, hidden time and vast cosmic cycles, magic squares and compass rings, equalization, self-realization.

Accomplishments with Relevance in the 21st Century: Cultural shifts NEVER succeeded in subjugation of Xi Wang Mu, the Divine Mother. She remains the great feminine principle, the Tai Yin, the embodiment of non-duality, complete

within herself, despite efforts to marry her off. She guards the double mechanisms of the dipper the Handle (Jade Crossbar) of the five Constants (Elements) and the ladle as well as the invisible stars, Fu and Pi. She governs over the external and internal structure of the North Bushel and the regulation of yin and yang and the nine heavens. As non-dual she is purple, equal parts red and blue. She embodies and governs Taoist arts of self-transformation, realization, and internal alchemy which include meditation, breath, movement, medicine, and elixir practices. She is a wisdom keeper of the Tao as well as its source, its taproot and the legendary shamanic emperors Shun and Yu studied with Xi Wangmu, as well as Lao Tzu.

Queen Mother of the West: The Great Mother Archetype

Queen Mother of the West: The Great Mother Archetype

Guardian of the cosmic axis, the venerated Queen Mother of the West is known by many names. Her myths and creation stories abound with powerful parallels to female goddesses, spirits and shamans around the globe. As Mother of the World, Primordial Heavenly Being, Guardian of the Gateway between Heaven and Earth, and the personification of Tao, she stands as a powerful foundation to Chinese philosophy and the Tao de Ching. She also embodies many of the qualities of Great Mother myths and archetypes from around the globe.

The Tao is called the Great Mother: empty yet inexhaustible,

empty yet inexhaustible,

it gives birth to infinite worlds.

It is always present within you.

You can use it any way you want.

- Tao Te Ching 6 – Lao Tzu, Stephen Mitchell, translation, 1998

The valley spirit never dies;

It is the woman, primal mother.

Her gateway is the root of heaven and Earth.

It is like a veil barely seen.

Use it; it will never fail.

Tao de Ching 6 – Lao Tzu, Gia-Fu Feng, Feng Jia-fu,

Jane English translation, 1989

Archeologist, Marija Gimbutas identifies the primary themes of Goddess mythology and symbolism with birth, death, renewal of all life and the cosmos.

Symbols and images cluster around parthenogentic (self-generating) Goddess and her basic function as Giver of Life, Wielder of Death and not less importantly, as Regeneratrix, and around the Earth, Mother, the Fertility Goddess young and old, rising and dying with plant life. She was the single source of all life who took her energy from the springs and wells, from the sun, moon and moist earth. This symbolic system represents cyclical, not linear, mythical time. In art this is manifested by the signs of dynamic motion: whirling and twisting spirals, winding and coiling snakes, circles, crescents, horns, sprouting seeds and shoots. (1989, xix)

Almost all mythology includes a creation story in which The Great Mother gives birth to herself and the cosmos through parthenogenesis. All life emerges from the egg, which splits in two to represent the polarities of the Universe—male and female, yin and yang, hot and cold, sun and moon, day and night, each a complement to the other and representative of the ever-changing balance that maintains harmony in the cosmos. Earth Mother myths are populated with imagery of wild beasts and serpents, water and fire, love, sex, death, and the underworld. While the stories may vary, and the characteristics of those that populate them may change over time the archetype they represent of a powerful female divinity remain the same from indigenous North American narratives to Neolithic Europe to Asia.

Almost all mythology includes a creation story in which The Great Mother gives birth to herself and the cosmos through parthenogenesis. All life emerges from the egg, which splits in two to represent the polarities of the Universe—male and female, yin and yang, hot and cold, sun and moon, day and night, each a complement to the other and representative of the ever-changing balance that maintains harmony in the cosmos. Earth Mother myths are populated with imagery of wild beasts and serpents, water and fire, love, sex, death, and the underworld. While the stories may vary, and the characteristics of those that populate them may change over time the archetype they represent of a powerful female divinity remain the same from indigenous North American narratives to Neolithic Europe to Asia.

The Queen Mother of the West (Xi Wang Mu) is the Great Mother Archetype and powerful female goddess. She is symbol of the unity of life in nature, and the personification of all that is sacred and mysterious on Earth. A supreme matriarch, her roots which likely pre-date even the bone oracles, from the Shang dynasty of China (c. 1600-1046 BCE) predates Taoism and contains all of the great qualities of mythic creations, from monster to creatrix to supernatural being.

Residing on Kunlun mountain between heaven and earth she is a cosmic weaver who maintains the universe and has dominion over the sun, moon and stars. She can bring epidemics and cure them, and is linked to the tree of life, the axis mundi that connects heaven and earth, the starry heavens and the Big Dipper. As the keeper of immortality, she bestows good fortune and has a strong association with the natural world including trees, flowers, birds and animals. As guardian of the peaches of immortality she has the ability to generate new life, bring death, provide regeneration and bestow everlasting life. She has links to both yin and yang which suggest that she is complete and independent.

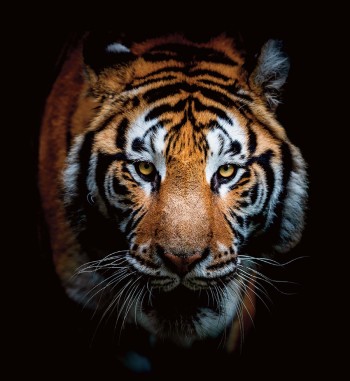

During the Zhou dynasty, the longest in Chinese history (1046-256 BCE) she is ferocious and wild with teeth of a tiger, the tail of a leopard, a jade ornament in her hair, and a staff. She was believed to be responsible for plagues and pestilence. However, like many goddesses she has a duel nature and comes to be associated with healing, portrayed with a curative, kindly, and peaceful side, she had the ability to stop epidemics. Once she is adopted into the Taoist pantheon, she also becomes known as the goddess of life and immortality. In the 4th Century BC she is described by Taoist writer Zhuangzi as one of the highest deities having obtained immortality and celestial powers.

Knowledge of her grew in the second century with the opening of the silk road and the linking of the northern and western parts of China. During the Tang dynasty 618-907, a time when poetry flourished, she became quite popular and is depicted in many poems.

In artwork she is often depicted holding court in her palace on Kunlun Mountain, surrounded by goddesses and female spiritual attendants. Her gardens were rich with healing herbs and fruit and her peaches, which were known as the peaches of immortality, that would only ripen every three thousand years.

Today, Xi Wang Mu stands as a powerful symbol of female strength and independence. Jung understood the power of these primordial images and viewed them as though they are psychic organs to be treated with the utmost respect:

It is only possible to live the fullest life when we are in harmony with these symbols; wisdom is a return to them. It is a question of neither belief nor of knowledge, but of the agreement of our thinking with the primordial images of the unconscious. They are the unthinkable matrices of all our thoughts, no matter what our conscious mind may cogitate. (1960/1969b, p. 403)

The Queen Mother of the west resides on Kunlun Mountain. This mysterious numinous mountain is located in the far west, a place outside of time and space, where joy prevailed and music, poetry and divine banquets were held. In some sources the mountain is associated with Jade the essence of yin. The sacred mountain was also the home to dancing frogs, and the moon-hare pounding out magical elixirs. Xi Wang Mu dwelled here among shamans, attended to by the Jade maidens, and protected by many fantastic beasts including the dragon, phoenix, three azure birds, and the moon-hare who pounds magic elixirs. She is guardian and nurturer of the Peaches of Immortality, and here in her golden palace the immortals gather to partake of a sacred feast and renew their immortality every 3000 years. Through her strong association with peaches her mythic roots may well link to ancient Persia as most European languages link the peach to Persia. There is also a theory that in ancient times Golden peaches were sent to China from Samarkand, the second largest city in Uzbekistan that held a central position on the Silk Road between China and the West.

Kunlun Mountain is the home of the axial tree, in this case embodied by the peach tree of immortality, which connects heaven and Earth and can be likened to a womb from which all creation comes. The cosmic peach tree described as 3000 miles around embodies the Tree of Life and can also be viewed as a ladder of ascension that enabled deities to travel from the earthly plane to the heavens. In India, Tibet, and Siberian Shamanistic practices the ladder may be represented as a stairway, bridge, tree, or rope that is used to transcend space and time.

The Queen mother also has strong links to Shamanism. In the Songs of Chu, a primary source on Shamanism Kunlun mountain is described as the road one must travel to journey between the worlds. Additionally, in the Shan Hai Jing and many other sources Xi Wang Mu is linked to the tiger an animal with strong shamanistic roots throughout Asia. Some narratives identify the goddess as a Snake Shaman. In numerous cross cultural myths, snakes play an important roll in the secret teachings and mysteries surrounding life, death, and immortality. In some early myths of Athena, she is viewed as the fearsome Lady of the Snakes. Robert Graves believed that Athena may well be an incarnation of the Libyan snake goddess Neith. Gimbutas argues that during the Neolithic period, in the Minoan culture of Crete, there was a Mistress of the Waters whose physical form embodied the snake, as a fertility goddess and bringer of the life-giving rain.

The goddess is associated with sound and music. The Jade Maidens who reside with her on Kunlun Mountain are depicted as dancers and musicians that play chimes, flutes and jade singing stones. One source describes them as whistling or making a clear prolonged sound not unlike that of throat singing of today.

Spiritual ascension, linked to the number seven, can be found in many religious traditions, including Islam,

“See you not how Allah has created the seven heavens one above another, and made the moon a light in their midst, and made the sun a lamp” (Sura 71:15–16)? In a Taoist meditative tradition, the adept climbs a ladder of seven stars to reach the center of the bushel, which governs the spirit and corresponds to the highest of the three supreme heavens (Robinet, 1993, p.222).

The number seven appears in narratives surrounding the Queen Mother, as early as the Han dynasty the Double Seven festival was celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month at the seventh hour. Perceived as an accessible goddess who traveled between heaven and earth, this was the time that Xi Wang Mu would spend time in the world of humans and cosmic energy would be in perfect balance. During this same period the number seven appears in descriptions of The Queen Mother's meeting with Han Wu ti (who reigned from 141 to 87 B.C.E.). In the Po-wuchih (The Treatise on Research into Nature, ascribed to Chang Hua, third century C.E.) the emperor is described as welcoming the Queen Mother of the West on the seventh day of the seventh month, at the seventh division of the clock. In this account and others, the Emperor is seeking the peaches of immortality, which he does not obtain.

The Queen Mother, like Demeter is also a goddess of agriculture and fertility, responsible for rain, and grains and bringing an end to poor harvests and drought. Additionally, just as Demeter she can also anger and cause great destruction, including deforestation and poor harvests. Hsi Wang Mu's negative side could erupt in outbreaks of anger which, if powerful enough, fomented cosmic cataclysms, as occurred when learning that the moon goddess, Ch'ang-O, had stolen the brew of immortality that she alone had the power to distribute (Knapp, 1997).

Divine Feminine Teacher and Taoism

The archetypal Great Mother is an embodiment of Earth itself containing both benevolent life-giving qualities and darker aspects, she gives, and she withholds. Like Demeter, teaching the Eleusinian Mysteries, the most secret religions rites of Ancient Greece Xi Wang Mu is a teacher who initiates and governs over meditation, alchemy and transformation. Cahill identifies her as the source of wisdom that the Yellow Emperor learned from and as the master of Taoist teachings. Shang qi’ng Taoism describes a meeting between Lao Tzu and the Queen Mother, depicting the Queen Mother as superior to Lao Tzu and crediting her with authorship of the Tao de Ching. Although later texts attempt to place her in an inferior role to Lao Tzu and depict the queen mother as paying homage to him. In artwork and some early myths, she is depicted with wild untamed hair, tiger’s teeth and leopard’s tail to match a fierce wild demeanor. Some scholars believe that as she comes to be associated with the birth of Taoism she is elevated to a more regal stature as the beautiful ruler of heaven accompanied by the phoenix a symbol of eternal life. There is a Taoist Temple on Mt. Tai with a beautiful turquoise pond, that is identified as the Queen Mothers Pond.

Understanding the mythic depth of the Queen Mother of the West deepens not only our understanding of Chinese philosophy and the origins of Taoism but she provides us with keys to recognize how we might embrace Tai Yin, the Unified whole.

Myths provide an entire cosmology compatible with a culture's capacity for understanding, they establish a transcendent context for our brief existence here on earth, they validate the values which rule our lives, they ensure that cohesion of cultures and the worth of individuals by releasing an archetypal response at the deepest levels of our being, and they awaken in us a sense of participation in the mysterium tremendum et fascinans which pervades the relationship between the cosmos and the Self. (Stephens, 2002, p. 41, italics in text)

Through common language and themes, myths serve as guides to structure what unfolds in daily life, providing form and meaning offering keys that aid us in understanding our very existence in the cosmos, meaning that enriches our lives.

Meaninglessness inhibits fullness of life and is therefore equivalent to illness. Meaning makes a great many things endurable—perhaps everything. No science will ever replace myth, and a myth cannot be made out of any science. For it is not that “God” is a myth, but that myth is the revelation of a divine life. (Jung, 1961/1989, p. 340)

Subjugation of Female Power Archetype

Joseph Campbell identifies four distinct types of creation stories that are universal. These include creation stories in which the world is born from the goddess alone. This moves toward creation that arises from goddess and consort, to creation arising from the body of a goddess who is controlled by a male deity to creation stories attributed to the unaided male god alone.

Each of these different aspects of origin represents movement away from Earth Mother creation stories, to one in which sexual subordination of women becomes institutionalized and myths are rewritten to suit the patriarchal rulers. These events from ancient times to modern day are reenacted throughout history and can be seen in the evolution of the Queen Mother of the West. Although many attempts are made, throughout the ages, they never completely succeed in diminishing her power.

Beginning in the Han dynasty, (206 BC–220 AD), considered a golden age in China, we see examples of Xi Wangmu subordinate to great men who attempt to marry the goddess. In one version of the myth she is wed to the Jade Emperor which divests her of her autonomy and originality. Together they have many children, including three powerful daughters Zhu-sheng-niang-niang a goodessess of fertility, Yen-kuang niang-niang protector of the blind with the ability to grant sight, and Zhinu who falls in love with a human cowherd, perhaps a story that is not too dissimilar from that of Aphrodite and Anchises.

The Jade Emperor’s masculine nature is always depicted as level-headed and rational, while Xi Wangmu is seen as wild and untamable an embodiment of feminine yin energy. Their union is also viewed as a way to define yin and yang, where the Jade Emperor’s masculine energy is viewed as the more positive rather than the powerful, wild and strong independent women who is the guardian of all women Taoists, projecting power, independence and the ultimate yin.

In another version of the legend she resides as an immortal in a forested garden at the Jade Emperor’s palace. In this setting she is surrounded by female companions and magical creatures and tends to many rare herbs and plants as well as the peaches of immortality.

In the Chronicle of the Emperor Mu (3rd or 4th century A.D.), she is a beautiful and cultured queen who exchanges gifts and engages in political discussions with Emperor Mu, in these references she is depicted as the daughter of the God of Heaven.

Although there are myths which link her to the MU goddess of the East, the Sun and the Moon, Xi Wangmu is also linked to Dong Wang Gong, Lord of the Sky, who is said to have ruled in the East, their union creates heaven and earth and all of humanity.

Her subjugation is not always done in a positive light, in some she is represented as almost vampiric, taking the essence of young men and boys in order to maintain her immortality.

Whenever she had intercourse with a man he would immediately fall ill, yet she herself was fair of colour and form, glowing with beauty and needing no rouge or fard. Feeding on nothing but milk, she played the five-stringed lute, so that her heart was always harmonious, her thoughts composed, and no other desires plagued her. Having no husband, she liked to couple with young men and boys. But such secrets must not be spread abroad, lest other women copy the methods of Hsi Wang Mu. (Needham, 1983)

Rewriting Myth for Political Gain

Although myths change through time, regions, religion and politics a modern example of this are the attempts by China to rewrite the mythic narratives of the Queen Mother of the West as historical fact to discredit any separatist claims to the region of Xinjiang. This revisionist attempt is designed to further China’s rights to the restive northwestern region annexed by China in 1949. The region which today is populated by many nationalities from the Eurasian continent is a hub of the ancient Silk Road, a place where may diverse cultures assembled. Archeological discoveries in the region date back to the Neolithic period.

Among the new historical narratives put forth are claims of strong ties between The Queen Mother and Yu the great who saved the world from floods. Stories of King Mu are also recast to make the claim that as early as the Neolithic period, he journeyed to the western lands to visit with the leader of a matriarchal society known as The Queen Mother of the West. Their relationship is cast as that of equals engaged in a peaceful cultural and material exchange. In this way, modern historians attempt to make the claim that the people of the Central Plains and Xinjing, have always been connected and were engaged in peaceful exchanges as early as the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE).

Embrace the Divine Teacher and Initiator

Embrace the Divine Teacher and Initiator

Cahill (1993) identifies Xi Wang Mu as a divine teacher, initiator of mystic seekers, and in many cases the ultimate origin of the teachings and practices of Taoism. She governs the Taoist inner alchemy, the arts of transformation, meditation, breath and movement practices, as well as herbal medicines and elixirs. She is portrayed as a master of Taoist scriptures, with a library of the greatest books on Kunlun Mountain.

During these challenging divisive times it is of critical important to embrace the rich legacy of the Queen Mother of the West. Her teachings guide us toward a remembrance of strong female leadership, respect for the natural world and all its beings and the principal of Tai Yi to be fully whole engaging in transformation of body, mind and spirit.

Iconography of Xi Wangmu

Kunlun Mountain (Jade Mountain): Home to the Queen Mother of the West. Kunlun is also the place where a milieu of Chinese gods resided. The fabled Garden of the Western Paradise is situated here in this remote part of

western China between Tibet and Xijiang. Historically, the Kunlun mountain range was part of the Silk Road, with numerous caravans traveling between China and Persia, trading silks, spices, gold, and culture. This is likely how the peach made its way to Persia. Xi Wangmu’s palace is said to be a perfect paradise, the meeting place where the deities convened and a cosmic pillar where communications between deities and humans were possible. Here she was surrounded by female spiritual attendants, who aided in the guarding of yin essence. The peach tree, where the peaches of longevity grow, and ripen every 3000 years is also situated in her garden paradise, which also contains many herbs used to make special elixirs for healing and transformation.

Azure Birds: There are three azure birds that abound in Xi Wangmu art and literature. They are part of her entourage of shamanic spirits and emissaries. It isfrom these birds that she receives nourishment and sustenance, they also circle Kunlun Mountain to guard yin essence.

Azure Birds: There are three azure birds that abound in Xi Wangmu art and literature. They are part of her entourage of shamanic spirits and emissaries. It isfrom these birds that she receives nourishment and sustenance, they also circle Kunlun Mountain to guard yin essence.

Sheng Headdress: Though some interpret the head ornament as a victory crown, Xi Wangmu is seen in early reliefs wearing what most think is a sheng headdress comprised of a horizontal band with circles at the end resembling ancient depictions of the constellations. The sheng is associated with the loom and identifies Xi Wangmu as a cosmic weaver, controller of immortality and keeper of the stars, constellations, and the five bushels. Sheng gifts were

given on stellar holidays especially the Double Seven festival, when the gates open between the worlds.

The Grindstone: This is the inception point, the womb from with all creation is ground, the place where the axial Tree, the cosmic axis, unites heaven and earth, it is the shamanic vertical axis for journeys between the worlds.

Jade Maidens: The Jade Maidens are the ecstatic dancers and musicians who accompany the goddess. They play chimes, flutes, lutes, mouth organs and jade singing stones. These are the esteemed teachers of Taoist mystics, servers of divine foods, as well as mystic revelations of hidden time.

Fantastic Beings and Shamanistic Helpers and Guides: The sacred abode of The Queen Mother of the West has many shamanistic emissaries in addition to the yin essence guarding Jade Maidens and azure birds, there are three footed crows, nine tailed foxes, dancing frogs and a moon-rabbit who pounds magical elixirs of transformation and transportation. Phoenixes, chimera, spirits riding on white stags, and the five colored dragons also support the goddess. She is clearly at home with the wild things and magic, her own shamanic roots and her early depiction that ties her to the tiger and leopard with whom she shares kinship in the western wilderness.

Fantastic Beings and Shamanistic Helpers and Guides: The sacred abode of The Queen Mother of the West has many shamanistic emissaries in addition to the yin essence guarding Jade Maidens and azure birds, there are three footed crows, nine tailed foxes, dancing frogs and a moon-rabbit who pounds magical elixirs of transformation and transportation. Phoenixes, chimera, spirits riding on white stags, and the five colored dragons also support the goddess. She is clearly at home with the wild things and magic, her own shamanic roots and her early depiction that ties her to the tiger and leopard with whom she shares kinship in the western wilderness.

The West and Chinese Medicine Correspondences: Technically, Queen Mother Xi Wangmu rules over all elements in Five Element Theory since she controls the sun, moon and stars the five bushels, yin and yang, and the cauldron of creation. However, she has a special connection to the west as part of the death of the sun, our divine spark, and through her many associations with funerals, tombs, the afterlife, immortality, and as guide of vast cosmic cycles. Her shamanic form with tiger’s teeth, leopard’s tail and whiskers, is also an ancient connection to the west.

Correspondences: The Queen Mother of the West relates to all the elements. However, her most common association is her direction which is the West. Her element is Metal, the season of Autumn (the harvest time), and her climate is dry. Her color is white, a sound associated with her is weeping and the associated emotion is reverence for all life coupled with grief. Her associated organs are the Lung and Large Intestine. Her sense organ is the nose and her skin and hair are of primary importance. She metabolizes minerals and oxygen in her high mountain domain and her Qi energy is Po a clear connection to all of the animals. Her virtue is righteousness and her greatest virtue is Honoring Protocol and Compassion. She oversees rituals, is without question an alchemist able to bring things to completion and distill their essence creating the immortal elixirs of transformation.

The Toad, Tortoise and the Hare: The toad and hare are fertility symbols that are unequivocally associated with the moon in many world mythologies, especially the Chinese. Toads are amphibious and spend the initial part of their lives underwater until they shed their skins, and then live on land or land and in water, speaking to the immortal and non-dual qualities of Xi Wangmu. The tortoise is an icon associated with earth, earth healing and emergence and creation of the world and all life. The peaches of immortality in the Western Paradise gardens were grown beside the Tortoise Pond symbolizing new creation and immortality. The hare or rabbit is a common symbol associated with Xi Wang Mu, and Chang-e the moon goddess. The rabbit is seen pounding the elixir of immortality, of life, with his mortar and pestle, holding the yin essence for eternity.

The Toad, Tortoise and the Hare: The toad and hare are fertility symbols that are unequivocally associated with the moon in many world mythologies, especially the Chinese. Toads are amphibious and spend the initial part of their lives underwater until they shed their skins, and then live on land or land and in water, speaking to the immortal and non-dual qualities of Xi Wangmu. The tortoise is an icon associated with earth, earth healing and emergence and creation of the world and all life. The peaches of immortality in the Western Paradise gardens were grown beside the Tortoise Pond symbolizing new creation and immortality. The hare or rabbit is a common symbol associated with Xi Wang Mu, and Chang-e the moon goddess. The rabbit is seen pounding the elixir of immortality, of life, with his mortar and pestle, holding the yin essence for eternity.

Peach - Symbolism

In China and Japan, the peach is associated with fertility, immortality and long life. It is one of the three Blessed Fruits in Buddhism. The other fruits are citrus (happiness) and pomegranate (fertility). A Chinese concept is that the peach is a world-tree, a Mother Goddess and the peach is her shen, her spirit, her life substance.

Today peaches are grown all over China and continue to have symbolic, magical, and nutritional value. They have appeared in many religious rites and ceremonies, and they are frequently found on alters of family shrines. In the book Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics there are many accounts of foreign influence on early Chinese life and culture and the many exotic wares that were brought to China particularly during the T’ang Dynasty.

Today peaches are grown all over China and continue to have symbolic, magical, and nutritional value. They have appeared in many religious rites and ceremonies, and they are frequently found on alters of family shrines. In the book Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics there are many accounts of foreign influence on early Chinese life and culture and the many exotic wares that were brought to China particularly during the T’ang Dynasty.

Among these were fancy yellow peaches, (the size of goose eggs and golden) from the great city of Samarkand founded in 700 BC by the Sogdians of Indo-Europe. This kingdom in Northeastern Uzbekistan was conquered by Persia and then by Alexander the Great, which led scholars to believe that peaches originated in the west. However, peaches also figure in the Japanese myth of Izanami and Izanagi recorded in the Kojiki ancient chronicles, predating the golden gifts and perhaps more akin to the earlier Sumerian myths of Inanna and Dumuzi.

Much literature points to the fact that peaches actually originated in China and were grown in the Northern regions and wild peach varieties including the Maotao and Yietao are still cultivated today in the remote fringes of China. Peaches are mentioned in Chinese literature as far back as 10th century BCE, and the history of cultivation goes back even further. Pits and other archeological remains date to 5,000 BCE in the Northern and Western regions of China and Tibet.

The peaches of Samarkand are a newer variety that came after the birth of Christ and were successfully transplanted in Imperial orchards in the T’ang Dynasty (618-907CE). They gained in popularity particularly in the Sung Dynasty (960-1279CE) where white and yellow peaches were common elements of the Chinese diet. Travelers along the caravan routes (Silk Road) brought the peach seed to Persia where they were exported to Greece. Theophrastus, Greek philosopher, botanist, and student of Aristotle named the peach. Unaware of its Chinese origin, he called them Persikon Malon, meaning Persian apple, which became pesca then peach.

Peaches are commonly found in folklore, religion, paintings, literature and handicrafts. They are beloved in popular culture where they bring luck, abundance, protection, and offer immortality. Every part of the peach is used and valued—the peach wood is used for amulets to ward off demons, the blossoms bring the element of beauty and magic to paintings and embroidery, and the fruits pure deliciousness is a culinary delight. The peach kernel is an important herb in the Chinese apothecary of medicine.

Xi Wangmu and the Immortal Peach

Xi Wang Mu is responsible for the eternal existence of the gods, through her careful cultivation of the peach tree, that blooms every 3,000 years. She harvested the fruit and created the magic elixir that bestowed immortality. Every three thousand years the gods had to renew their longevity by coming to the Garden of the Western Paradise to eat the peach of long life and drink the elixir of immortality. This Western Garden is thought to reside in a remote part of the Kunlun Mountains, the home of the life restoring herbs tended by the Queen Mother Xi Wangmu. She has tremendous power as an alchemist famous for her transformative elixirs including the elixir of immortality for the gods.

Reference

Cahill, S. E. (1993). Transcendence & divine passion: The Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Chen, M.E. (1974) History of Religions, (14: 1), pp. 51-64

Dashu, M. (2010). Xi Wangmu, the shamanic goddess of China. Available at https://www.academia.edu/4075136/Xi_Wangmu_the_shamanic_goddess_ of_China

Despeux, C. & Kohn, L. (2003). Women in Taoism. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press

Knapp, B.L. (1997). Women in myth. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the Goddess, New York: New York: Thames & Hudson

Irwin, L. (1990). Divinity and salvation: The great Goddesses of China. Asian Folklore Studies. (49) p. 53-68

Author Unknown. The peach as a kami and Mother Goddess, the symbol of fertility and immortality, Japanese Mythology and Folklore, retrieved 1/15/2020, from https://japanesemythology.wordpress.com

Jung, C. G. (1969b). Psychology and religion: West and East (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.), from the Collected works of C. G. Jung, volume 11, Bollingen Series XX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

Knapp, B. L. (1997). Women in myth, Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Needham, J. 1983. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neumann, E. (1972). The great mother: An analysis of the archetype (R. Manheim,Trans.). Bollingen Series XLVII. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bollingen Series XLII. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1955)

Newman, J. M (2000). Peach: A Most Classical Fruit, Flavor & Fortune, (7,1), pp. 5-26.

Laozi., Feng, G., & English, J. (1998). Tao te ching. New York, New York: Vintage Books

Rippa, A. (2013). The China Journal. Re-writing mythology in Xinjiang: The Case of the Queen Mother of the West, King Mu and the Kunlun, No 71, DOI: 1324-9347/2014/71010-0003.

Robinet, I. (1993). Taoist mediation: The Mao-shan tradition of great purity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Stevens, A. (2002). Archetype revisited: An updated natural history of the Self. London: Brunner-Routledge. (Original work published 1982).

Wang, R. R. (2003). Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period through the Song Dynasty. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Wu, J. (2016). Mythical Image of Queen Mother of the West and Metaphysical Concept of Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas. Journal of Humanities and Social Science (21:11) pp. 39-46.